Have you heard the one about the patient who complains to the doctor, "My kidneys are hurting"? I've heard that story, quite a few times, and believe me, it's no joke. Usually, after eliciting a medical history and performing the appropriate physical examination, revealing the back muscles to be tender to superficial palpation and painful to minor body movement, I have been able to reassure the patient that the problem is actually just a muscular backache, not a "kidney" condition.

Why is this story worth telling? Because of the nature of the reaction that such news has so often elicited. "It isn't my back," the patients say, while grasping their sore back muscle with their hand. "I wouldn't have taken off work and paid to come to the doctor if it was just a backache. It's something deeper."

So what to do? Apologize, send the perfectly normal urine specimen to the lab for a culture, prescribe an antibiotic, and order a renal ultrasound -- or perhaps a CT scan, for just a few hundred dollars more?

If you work as a salaried staff physician for a managed care health maintenance organization (HMO), as I have for 15 years [Late Note: Since this 1995 essay was written, I have subsequently retired from medical practice], you're in a double bind. On the one hand, there is subtle pressure, in the form of computer printouts tracking your "cost effectiveness," to avoid unnecessary testing. But common sense, a patriotic duty to help control spiraling healthcare costs, and confidence in one's diagnostic skills already militate in that direction, at least for me.

On the other hand, the HMO encourages patients to express their "feelings" about their "healthcare experience" by filling out a "How did we do today?" questionnaire, stuffed into their hands upon arrival, and with follow-up telephone calls conducted by a professional polling organization such as Gallup. "Reassuring" patients with a muscular backache that they do not have a more serious malady guarantees, in a substantial percentage of patients, a complaint that the doctor was "uncaring" and "didn't take my problem seriously." When asked by Gallup how "knowledgeable" the doctor was, you can imagine the response.

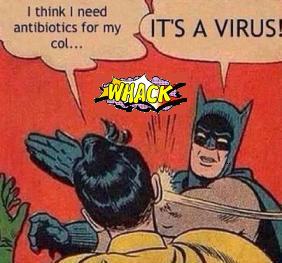

But to many doctors these days, even more dreaded than a patient with a simple backache is one with

a common cold. Most physicians cynically opt to prescribe an antibiotic to "satisfy" the patient --

his or her visit to the doctor thus becomes officially certified as having been "worth it." Dare

inform a patient with a cold that he or she doesn't need an antibiotic; that, in fact, antibiotics

are ineffective against cold viruses; that over-prescribing antibiotics is leading to the

development of resistant strains of bacteria; that once-curable diseases are thus becoming

untreatable; and that as a result, scores of thousands of deaths are now projected for the coming

decade. "He made me feel like an idiot" is a typical patient refrain following an attempt by the

healthcare "provider" (the managed care industry's knowledge-neutral term for "doctor" or

"physician") to so educate the healthcare "consumer."

But to many doctors these days, even more dreaded than a patient with a simple backache is one with

a common cold. Most physicians cynically opt to prescribe an antibiotic to "satisfy" the patient --

his or her visit to the doctor thus becomes officially certified as having been "worth it." Dare

inform a patient with a cold that he or she doesn't need an antibiotic; that, in fact, antibiotics

are ineffective against cold viruses; that over-prescribing antibiotics is leading to the

development of resistant strains of bacteria; that once-curable diseases are thus becoming

untreatable; and that as a result, scores of thousands of deaths are now projected for the coming

decade. "He made me feel like an idiot" is a typical patient refrain following an attempt by the

healthcare "provider" (the managed care industry's knowledge-neutral term for "doctor" or

"physician") to so educate the healthcare "consumer."

"Doctor" derives from the Latin word for "teacher." Had my high school friends been less competitive and "pre-med" oriented, I might have chosen a career as a junior high school science teacher rather than a physician. But peer pressure, and the realization that I could qualify for medical school, helped solidify my choice. Today, as frustrating as my job has become, school teachers have it infinitely tougher -- the present climate of "political correctness" is making it as impossible for many of them to control their classrooms and educate their students as it is for me to try to educate a patient. And the stress is taking its toll in terms of the number of visits that teachers are making to the doctor's office -- in the jargon of managed care, the school boards are extremely high utilizers of contracted services.

When I was a kid, students tended to behave in class and do their homework, and teachers were not pressured to hand out inflated grades so as not to "offend." Similarly, patients tended to exalt their doctors and rarely foisted demands upon them. I remember how my father would come home from the doctor's office shaking his head and nursing a sore rump, yet confident that the penicillin shot inflicted upon him for his cold would "knock it out." In that post-World War II era, even many doctors may not have appreciated the futility (except as a placebo) of throwing those newfangled antibacterial agents at a virus. Now patients demand antibiotics for clearly inappropriate reasons -- or else.

In his best-selling 1993 book, Healing Words: The Power of Prayer and the Practice of Medicine, Dr. Larry Dossey, co-chair of the Panel on Mind/Body Interventions at the NIH Office of Alternative Medicine, offers a rather unusual perspective on how medications exert their effects, at least in part. Extrapolating from the dubious work of parapsychologists in allegedly documenting the existence of psychic phenomena, Dossey suggests (p. 138) that "a physician's thoughts and beliefs [can] actually shape a patient's physiological responses [to medication] -- at a distance, even when the patient is unaware." Dossey and his book have been praised throughout the print media as well as on a number of national television programs. I suppose it was politically incorrect of me to skewer the book in my review for the Summer 1994 issue of Skeptical Inquirer (a relatively obscure though societally indispensable magazine), but someone needs to expose such blather for what it is.

As a doctor/teacher, I feel a naive inclination to enrich my patients' minds as well as treat their bodies. But in this politically correct New Age, a satisfying doctor's visit, like a trip to Burger King, means "having it your way." So when my next "cold" patient demands an antibiotic, rather than attempting to provide scientifically sound care, which only results in a complaint being generated, I think I'll give this tried-and-true response a whirl: "Yes, ma'am. And would you like fries with that?"